TensorJS - Writing a fast deep learning library for the browser

Posted on Thu 16 September 2021 in Machine learning

When I build Detext, I was looking for deep learning libraries for the browser. The main 2 options where

- Onnx.JS, developed by Microsoft but not actively maintained at the time

- TensorFlow.js, which is pretty mature and well maintained by facebook, but uses its own storage format for trained networks. Converting a trained Pytorch model to this format proved to be very challenging at the time.

So, what do you do when there's no viable inference library for executing your PyTorch/ONNX model? You write your own library of course. The requirements that I had for this library specifically where:

- Fast execution of reasonably sized models on most hardware and browsers. For me, reasonably sized meant a MobileNet on the harware that I had access to - a pretty shitty laptop and a Okish mobile phone.

- A "low level" PyTorch like interface for doing computations with tensors - eg.

being able to do something like

const a = new Tensor([1,2,3,4,5,6], {shape: [2,3]}); const b = new Tensor([1,2,3,4,5,6], {shape: [3,2]}); a.matmul(b);I wanted to have this, so that the pre- and postprocessing that most models typically need could be done as fast as executing the model itself. - A "high level" interface for executing models stored in the ONNX format.

In this article I want to go over some of the development challenges that I encountered when I wrote this library. You can find it on Github and install it from NPM.

Tensors and how they are layed out in memory

Deep learning frameworks are centered around the concept of a tensor - which to us computer programmers is basically a multidimensional array. Consider a multi dimensional array/tensor like the following one:

[[[1,2,3,4],

[5,6,7,8],

[9,10,11,12]],

[[13,14,15,16],

[17,18,19,20],

[21,22,23,24]]]

This tensor has 3 dimensions, which we call its "rank". The dimensions have a length of

[2,3,4] respectively, which we summarize as the tensors shape. The simplest layout

to store tensors in memory is called the contiguous layout - which basically

just stores the values in the order that you specify them, together with the shape of the tensor.

This layout allows you to have zero-copy reshapes of tensors, but not much else. While there is also the strided layout that allows you to have zero copy transpose and range selection operations, I chose to go with the contiguous layout, since its easy to implement.

Execution backends on the Web

While tensor operations are very straightforward to implement in Javascript, these implementations will not be fast enough to execute any reasonably sized model. Luckily there are other options for fast code execution:

- Webassembly, a binary instruction format that can give you faster runtime than simple Javascript - if optimized sufficiently.

- WebGL, a Javascript API intended for 2D and 3D rendering.

Webassembly

Webassembly (WASM) by now is supported by all major browsers. While you can in principle handwrite Webassembly in the WAT format, I chose to use Rust. Compiling to WASM is pretty well supported and wasm-bindgen even generates the JS boilerplate code for calling into WASM, and corresponding Typescript Type definitions for you. With this writing the WASM backend was way simpler than expected.

WebGL

WebGL was originally intended for 2D and 3D visualizations accelerated by GPUs. So how do you abuse this API to implement fast tensor operations?

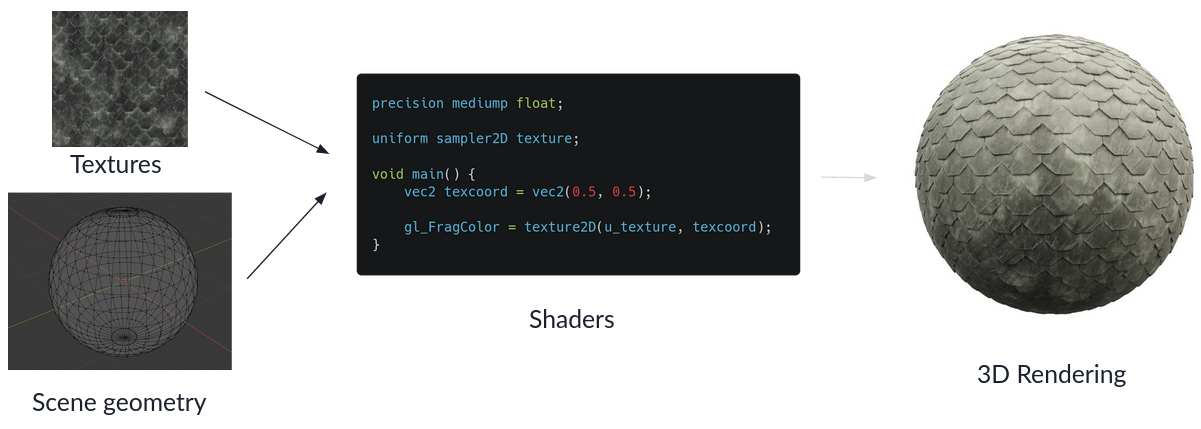

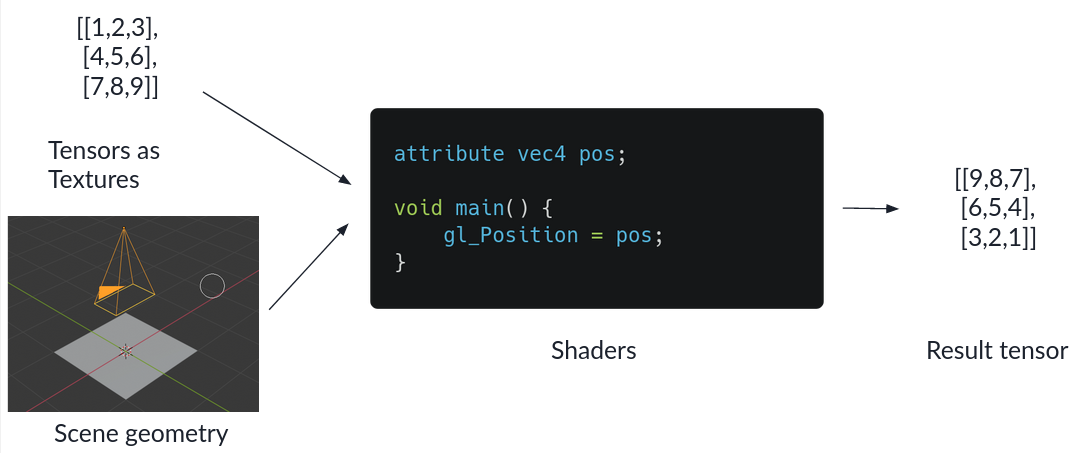

The traditional pipeline in WebGL looks a bit like this:

You feed the geometry of the scene and textures to the vertex and fragment shaders. The vertex shader determines the position of all vertices on the screen, while the fragment shader determines the color of each pixel on the screen - typically using the textures.

By setting up a very simple scene geometry of a single rectengular plane that fills up the whole screen, you can use the textures as your input tensors and treat the rendered output as the result tensor.

Doing this allows you to implement many operations by simply writing the correct fragment shader.

There is one detail that I'm going over here - which is the conversion of tensors to textures and back. For this you

- Represent the tensor in the contiguous layout

- Create a texture of fitting height and width. If the tensor has a size that is not conveniently dividable into integer width and height you create a texture that is slightly bigger than needed.

- You fill the tensor data into the texture pixels row by row. Since each pixel consists of 4 floating point values for the red, green, blue and transparent component, you only need 1/4th of the pixels of the size of your tensor.

In the fragment shader you of course also have to do this conversion between tensor indices and texture coordinates.

Considerations for fast speed

With this setup, its possible to implement quite a few tensor operations. But just running stuff in WebGL naively is not enough to get fast inference. For this you have to be very careful to move as little data as possible between the CPU and the GPU. When does this happen? Well for example when:

- A new shader gets compiled. This is super slow, and thus should only be done once for each shader

- Tensor values are transferred to the GPU

These two are maybe obvious, but there's a third case that can really slow down shader execution speeds. For many operations you have to provide additional information. Take the matrix multiplication operation for example. A rough implementation in GLSL, the Shading Language in WebGL, might look something like this:

uniform sampler2D _A;

uniform sampler2D _B;

uniform int shapeA[2];

uniform int shapeB[2];

uniform int transposeA;

uniform int transposeB;

float process(int index[2]) {

// Do the actual matrix multiplication

}

Next to the actual input tensors, which are passed in as textures accessed by samplers, we provide additional information like the shape of the both input tensors and if they are transposed. These uniforms are passed in from Javascript before running the actual shader:

var offsetTransposeA = gl.getUniformLocation(matrixMultProgramm, "transposeA");

gl.uniform1i (offsetTransposeA, 0 /* Or 1 if A is transposed */);

// Do the same for all other uniforms

This approach has the advantage, that you only ever need to compile one shader for one type of tensor operation.

Unfortunately, the calls to gl.uniform*, which transfer data from the CPU to the GPU, end up taking longer than the

shader invocations themselves. So what can you do to avoid the transfers between CPU and GPU? Compile

these uniforms as constants into the shaders themselves instead! The above programm would instead look something like

this, when compiled for two tensors of shape [3,4] and [4,5].

uniform sampler2D _A;

uniform sampler2D _B;

int shapeA[2];

int shapeB[2];

int transposeA;

int transposeB;

void initVars() {

shapeA[0] = 3;

shapeA[1] = 4;

shapeB[0] = 4;

shapeB[1] = 5;

transposeA = 0;

transposeB = 0;

}

float process(int index[2]) {

initVars();

// Do the actual matrix multiplication

}

Of course, the drawback with this approach is, that now you have to compile a new shader for each tensor operation with slightly different parameters. Compiling the shaders must be done in the browse and also takes a little time, so this is not for free either. To avoid doing this expensive compilation for shaders that might only be called once, TensorJS uses a hybrid approach:

- Operation invocations by default use a general shader, where parameters have to be passed in via uniforms

- For each invocation, TensorJS logs the parameters of the call. If the same parameters are used for

more than

kinvocations (wherekis some sensible threshold), a specialised shader is compiled.

In practice this means, that using a deep neural network needs a couple of forward passes for "warm up", before all necessary shaders are compiled. The upside is that after this warmup, its possible to run small CNN's (eg. a MobileNet) in real time! Check this example, which runs a MobileNet pretrained on ImageNet entirely in the browser.

Features of TensorJS

TensorJS has a few features beyond GPU support:

ONNX support

Onnx is an open exchange format for deep learning models supported by most deep learning frameworks and inference engines. Since my mine gripe with TensorFlow.JS was its lacking support for ONNX models, this feature had big priority for me. At the time of writing, 75 operators from the ONNX opset are supported, as you can see here. This makes it possible to run the most common CNN architectures!

Automatic differentiation

Although training a whole deep neural network in the browser is maybe a bit unrealistic, it is absolutely possible to do some finetuning of the last layer(s). To do this, some support for automatic differentiation is needed. For this, TensorJS builds a dynamic computation graph (when needed) and implements reverse mode automatic differentiation.

With this, it's possible to fine tune a model directly in the browser. In this example, a MobileNet is finetuned to detect, if the user is touching the face, and play a warning if this is the case. The nice thing about this is that no data ever needs to leave the users device!

Optimizers and models

To support the training of small models, TensorJS implements some optimizers, which work similarly to PyTorch:

const l1 = new Linear(1, 128);

const l2 = new Relu();

const l3 = new Linear(128, 128);

const l4 = new Relu();

const l5 = new Linear(128, 64);

const l6 = new Relu();

const l7 = new Linear(64, 1);

const backend = 'GPU';

const model = new Sequential([new Linear(1, 128), new Relu(), new Linear(128, 128), new Relu(), new Linear(128, 1)]);

await model.toBackend(backend);

let optimizer = new Adam(model);

// When training the model

const res = await model.forward([x]);

const los = computeLoss(res);

loss.backward();

optimizer.step();

optimizer.zeroGrads();

A small example where a simple MLP is trained on a simple 1D function is implemented here.

Possible extensions

There are of course, many things that TensorJS is missing, that could still be implemented:

- Usage of multiple threads in the WASM backend: Multiple threads can be used in Rust when compiling to WASM. Unfortunately, there are still browsers that do not support the necessary JS API, shared array buffers.

- Usage of SIMD instructions in the WASM backend: WebAssembly has a set of SIMD instructions. Together with threads, this

would greatly speed up the WASM backend. On the flipside, to guarantee backward compatibility, the WASM backend would have to implement up to

4 versions of each operator (with/without thread support

*with/without SIMD support) - WebGPU is an upcoming API for accessing GPU's from the browser that promises to get rid of many of the restrictions of WebGL. It has support for actual compute shaders, so all the hackery of using a pixel shader as a means of implementing tensor computations could potentially be eliminated.